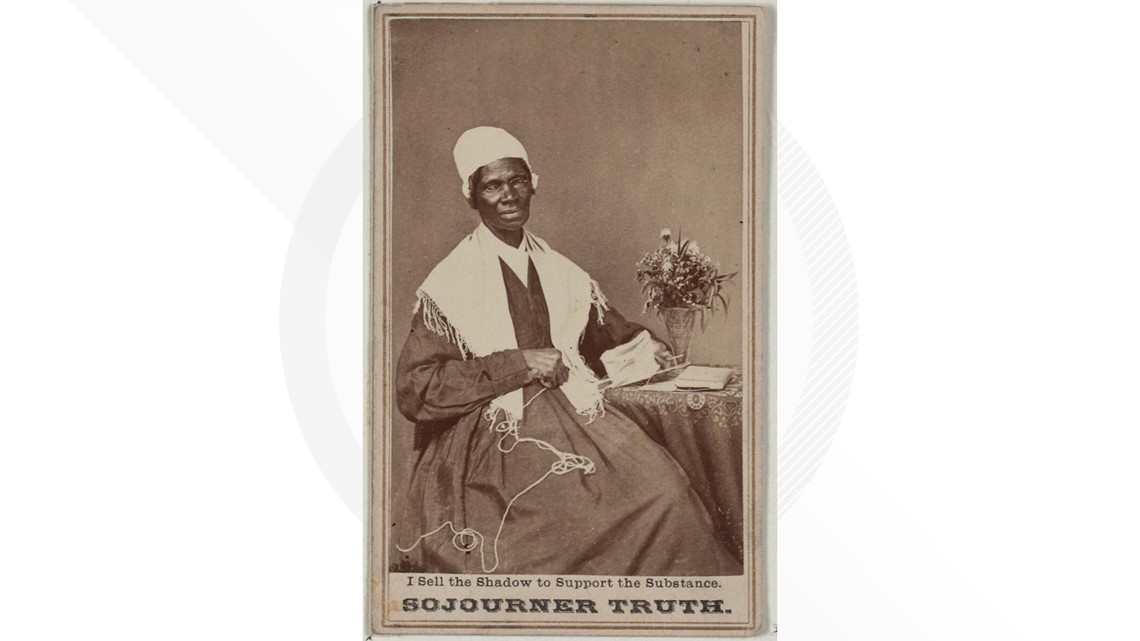

Sojourner Truth was an outspoken abolitionist and women’s rights activist in the 19th century. In 1851, Truth delivered what is now recognized as one of the most famous women's rights speeches in American history, known as “Ain't I a Woman?”

In early February, during Black History Month, a viral tweet claimed Truth never said the phrase “Ain’t I a Woman?” in her famous speech. It also claims Truth didn’t speak in Black southern vernacular, like the text of the speech implies.

“Did you know Sojourner Truth’s first language was Dutch? The version of her speech we are taught today ‘Aint I a Woman?’ was a version transcribed years later by a white woman who rendered her speech in what she imagined to be Black southern vernacular. That’s not how Truth spoke,” the tweet said.

THE QUESTION

Did Sojourner Truth say “Ain't I a Woman?” in her famous speech?

THE SOURCES

THE ANSWER

No, Sojourner Truth didn’t say “Ain't I a Woman?” in her famous speech.

WHAT WE FOUND

There is no evidence that Sojourner Truth said the phrase “Ain’t I a Woman?” while delivering her famous women’s rights speech in 1851. A newspaper article published a few weeks after Truth delivered her speech makes no mention of the well-known refrain. Instead, a transcription of the speech shows that Truth may have actually said, “I am a woman’s rights.”

Sojourner Truth was born into slavery in Ulster County, New York, in 1797. Her given name was Isabella Baumfree. She spent her early childhood on a New York estate owned by a Dutch American named Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh. Since she was enslaved by a Dutch family, her first language was Dutch, and she spoke English with a Dutch accent all her life.

In 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter and moved to New York City. She gained her freedom in 1827 once slavery became illegal in the state of New York. Truth worked in the city as a housekeeper until 1843, when she said she felt a call from God to become a preacher. When she left New York City, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and embarked on a tour as a public speaker and advocate for abolition and women’s rights.

On May 29, 1851, Truth delivered what would become known as her most famous speech at the Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech did not have a title at the time but later became known as “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Reverend Marius Robinson, an abolitionist who served as one of the secretaries of the convention, published his own account of Truth’s speech in the “Anti-Slavery Bugle,” the newspaper he edited, on June 21, 1851. Robinson and Truth were said to have been good friends, and it was documented that they went over his transcription of her speech before he published it, according to the Library of Congress and The Sojourner Truth Project.

Nearly 12 years after Truth delivered her speech in 1851, Frances Gage, a white abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, wrote and published her own version of Truth’s speech in 1863. Gage changed most of Truth’s words and falsely attributed a Southern slave dialect to her version of the speech.

“While Truth had been enslaved and escaped, this happened in the North. She never lived in the South and spoke only Dutch until she was nine years old,” Arlene Balkansky, a retired reference librarian at the Library of Congress, wrote in 2021.

“She could have retained some sort of Dutch accent when speaking English, but that would be nothing like the dialect Gage gave her,” Balkansky continued. “Emphasizing Southern slavery, though, would prove a more useful tool to Gage in 1863, rather than recalling already abolished slavery in a Northern state loyal to the Union.”

In 1996, historian Nell Irvin Painter examined both Robinson’s and Gage’s versions of Truth’s speech in her biography “Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol.” Painter concluded that Robinson’s version was more reliable than Gage’s account.

“Accounts of words in 1851 differ, and today the one historians judge the more reliable — because it was written close to the time when Truth spoke — is Marius Robinson's,” Painter wrote. “Gage crafted her ‘Sojourner Truth’ carefully, and her sensibility was remarkably modern. Her account is still compelling. But it is by no means the real Sojourner Truth.”

There is no evidence that Truth, who never learned to read or write, contested Gage’s version, according to Balkansky. She wrote that Gage’s account added to Truth’s fame while she continued to lecture until 1880.

“There were many obituaries following Sojourner Truth’s death on November 26, 1883, but one that appeared in multiple newspapers emphasized that her mind was ‘penetrating, clear, logical and original,’ her language was ‘grammatically correct,’ and her ‘enunciation and pronunciation was faultless,’” Balkansky wrote.

You can listen to Robinson’s transcription of Truth's speech on The Sojourner Truth Project’s website or below.