A cesarean section, or C-section, is the surgical delivery of a baby through an incision in the mother's abdomen and uterus. The procedure is typically performed by doctors when they believe it is safer for the mother, the baby, or both.

In December 2022, a viral TikTok video claimed that successful C-sections – ones in which both mother and baby survived – were performed for hundreds of years in Africa, before the procedure was common in Europe.

“The baby survived, the mother recovered well and they were given herbal treatments to promote wound healing," the TikTok user said.

THE QUESTION

Did African midwives successfully perform C-sections before it was common in Europe?

THE SOURCES

- National Library of Medicine

- Arizona State University

- University of Richmond

- “Notes on Labour in Central Africa” by British explorer Robert W. Felkin; published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, 1884

- “Cesarean Section: The History and Development of the Operation From Early Times” by J.H. Young; published by H.K. Lewis, London, 1944

- “A Librarian Looks At Cesarean Section” by M. Pierce Rucker and Edwin M. Rucker; published in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 1951

- “The development of scientific medicine in the African Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara” by J.N.P. Davies; published in Cambridge Journals Medical History, 1959

- Padmini Murthy, MD, health policy professor and the global health director at New York Medical College

THE ANSWER

Yes, African midwives successfully performed C-sections before it was common in Europe.

WHAT WE FOUND

African midwives did successfully perform C-sections before it was common in Europe. During the 19th century, European travelers documented witnessing successful operations, in which the mom and baby both survived, in parts of Africa, including Uganda and Rwanda, according to the National Library of Medicine.

The cesarean section has been a part of both Western and non-Western cultures since ancient times. Numerous references to the procedure appear in ancient Chinese, Hindu, Egyptian, Grecian, Roman and other European folklore. But the origin of the word “cesarean” and the early history of the procedure are both shrouded in myth.

The National Library of Medicine says that “cesarean” is commonly believed to have been derived from the surgical birth of Julius Caesar in 100 B.C. However, many historians say this story seems unlikely because Caesar’s mother, Aurelia, is said to have lived for many years after her son’s birth.

“At that time the procedure was performed only when the mother was dead or dying, as an attempt to save the child for a state wishing to increase its population,” the National Library of Medicine explains on its website. “Roman law under Caesar decreed that all women who were so fated by childbirth must be cut open; hence, cesarean.”

Many of the earliest successful C-sections — where both the mother and baby survived — were performed on kitchen tables and beds in remote, rural areas without access to medical staff or hospital facilities. Without a doctor on-site, this meant that the procedure could be carried out at an earlier stage in failing labor “when the mother was not near death and the fetus was less distressed.”

“Under these circumstances, the chances of one or both surviving were greater,” the National Library of Medicine said.

The first successful C-section recorded in the British Empire was performed by a woman in the early 19th century in Africa. James Miranda Stuart Barry, who was masquerading as a man and serving as a physician to the British army in South Africa, performed the operation in Cape Town in 1826 and successfully delivered a healthy boy, according to the Embryo Project Encyclopedia at Arizona State University and the National Library of Medicine.

Barry learned how to perform C-sections while attending medical school in Scotland, but had only seen two performed and both had proved fatal for the mother and fetus. In the early 19th century, antiseptic and anesthesia were not available and intense pain, as well as a high risk of infection, were commonplace with most C-sections, especially in hospitals during that time.

“Prior to the establishment of the germ theory of disease and the birth of modern bacteriology in the second half of the 19th century, surgeons wore their street clothes to operate and washed their hands infrequently while passing from one patient to another,” the National Library of Medicine said.

Later in the 19th century, travelers in other parts of Africa reported that they had seen indigenous people successfully performing C-sections while using their own unique medical practices. For instance, in 1879, British explorer and medical missionary Robert W. Felkin witnessed Ugandan male healers and midwives performing a C-section, in which the mother and baby both survived, during his journey through Central Africa.

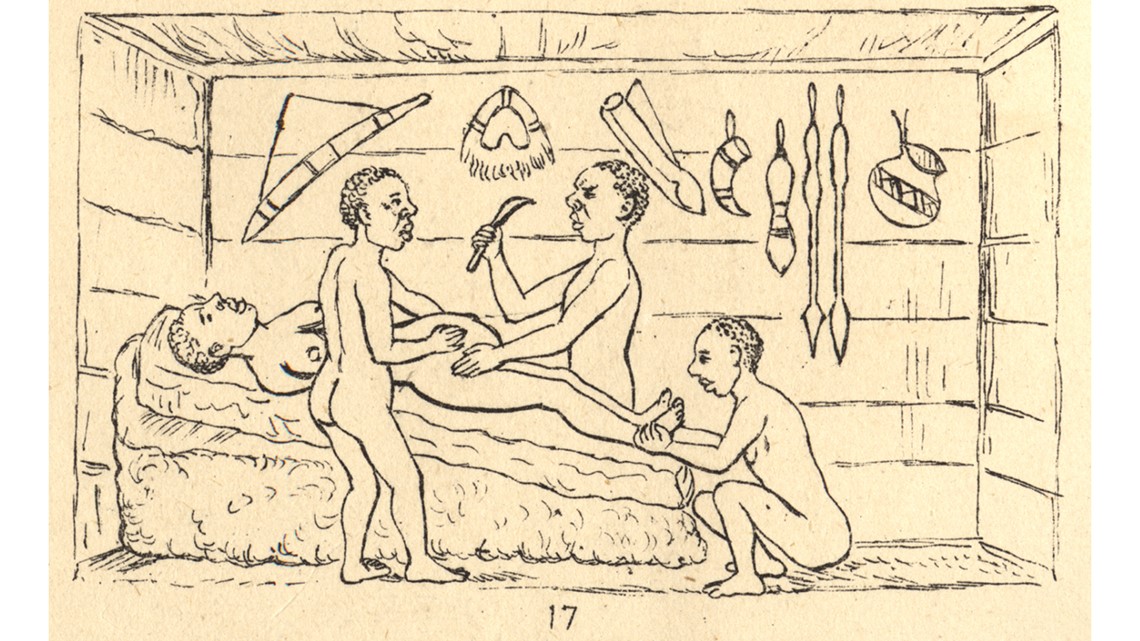

In an article published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal in 1884, Felkin wrote that while he was in Kahura, Uganda, he saw a healer from the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom use banana wine as a type of anesthesia to semi-intoxicate a woman in labor. The healer is also said to have cleansed his hands and the woman’s abdomen with banana wine and water prior to the surgery.

In his notes, Felkin wrote that the woman was fastened to the bed with bands of cloth, while an assistant held down her ankles, during the procedure. Another assistant steadied the woman's abdomen, while the healer proceeded to make a rapid cut to the abdominal wall and part of the uterine wall using a large, curved knife. After the incision, the infant was rapidly removed and given to another assistant after the umbilical cord had been cut.

According to Felkin’s notes, the healer kept firm pressure on the uterus until it was firmly contracted. Heat was also sparingly applied with a red-hot iron to minimize excessive bleeding. The healer did not use sutures, or stitches, to close the abdominal wound. Instead, Felkin detailed that the wound was pinned with seven thin iron spikes and fastened with a string made from bark cloth before it was dressed with a paste prepared from different roots. A banana leaf, which had been warmed over a fire, was placed on top of the dressed wound, according to Felkin, and a “firm bandage of mbugu cloth completed the operation.”

Since both the woman and baby recovered well after the C-section, Felkin concluded that the Bunyoro-Kitara’s technique had been well-developed and practiced for a long time.

“So far as I know, Uganda is the only country in Central Africa where abdominal section is practiced with the hope of saving both mother and child,” Felkin wrote.

Outside of Uganda, the National Library of Medicine says similar stories of successful C-sections were also performed in Rwanda, “where botanical preparations were also used to anesthetize the patient and promote wound healing.”

There is also documentation that African healers and midwives brought their knowledge of C-sections to the United States during the Transatlantic Slave Trade from the 16th to the 19th century.

According to the University of Richmond and the Embryo Project Encyclopedia, there is an account of a doctor in Virginia named Jesse Bennett performing the first successful C-section in the U.S. on his wife in 1794. Bennett is said to have performed the operation with the help and guidance of enslaved servants who were well-versed in the procedure.