In 2024, two broods of periodical cicadas will emerge in Illinois and the surrounding states at once: the 13-year Brood XIX and 17-year Brood XIII.

When Brood X emerged along the east coast in 2021, people on social media shared videos of cicada heads climbing trees, with several likening the bodiless creatures to zombies. “Zombie cicadas” is also a popular Google search in the lead-up to this year’s cicada season.

THE QUESTION

Are “zombie cicadas” real?

THE SOURCES

Brian Lovett, Ph.D., Division of Plant and Soil Sciences at West Virginia University

A study published in PLOS Pathogens, a peer-reviewed open-access medical journal

THE ANSWER

Yes, “zombie cicadas” are real.

WHAT WE FOUND

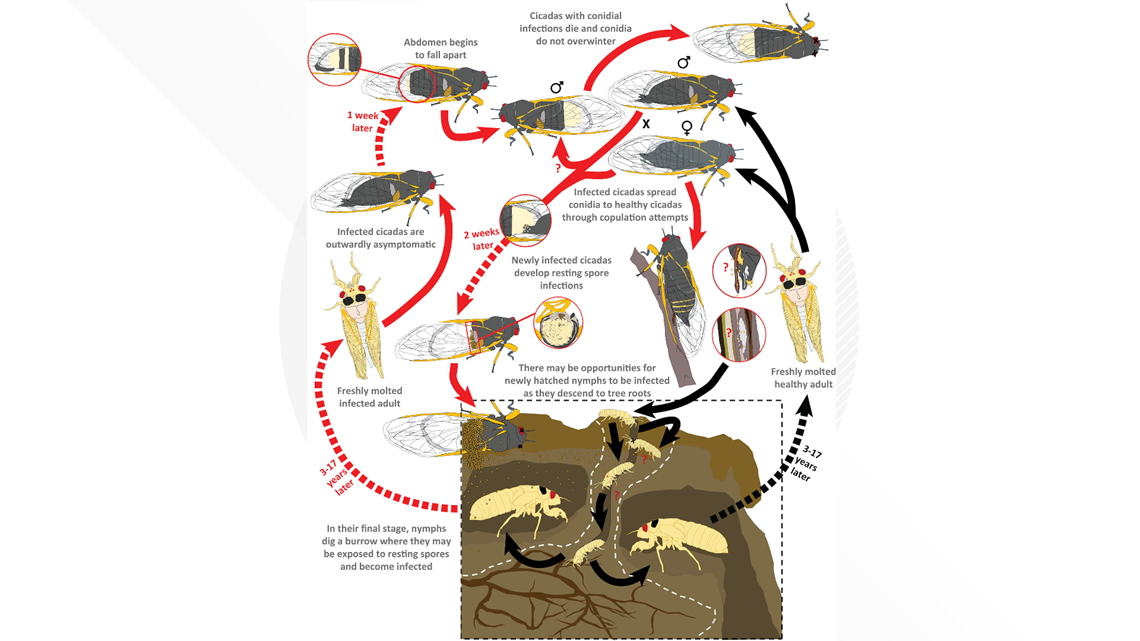

A team of researchers at West Virginia University in 2019 discovered that Massospora cicadina, a psychedelic fungus that specifically infects periodical cicadas, “contains chemicals similar to those found in hallucinogenic mushrooms.”

“The fungus causes cicadas to lose their limbs and eccentric behavior sets in: Males try to mate with everything they encounter, although the fungus has consumed their genitals and butts,” according to the researchers, which is why they have often referred to the infected cicadas as “zombies” and “flying saltshakers of death.”

Once periodical cicadas, like Brood X, emerge from beneath the surface after 17 years, their primary goal is to mate. In a study published by the WVU researchers in 2020, they state that several days after emergence, healthy periodical adult male cicadas begin to sing in order to attract adult female cicadas. Meanwhile, “the Massospora–Magicicada parasite–host system functions, in part, as a sexually transmitted infection.”

“Magicicada sexual behavior is highly stereotyped: males call and females respond with wing flicks, but healthy males never signal with wing flicks. When females remain unmated much beyond the onset of sexual receptivity, their responses become exaggerated with louder, more consistent wing flicks and sometimes even whole-body motions that appear to draw the attention of chorusing males,” according to the study.

“This exaggerated behavior is a form of hypersexuality that is consistent with age-related decreases in mate choosiness reported in cockroaches, medflies, parasitoid wasps, and other insects. In this context, hypersexuality observed in Massospora-infected cicadas is not surprising because infected cicadas remain unmated for their entire lives and may therefore exhibit increased sexual receptivity without any special manipulation by the fungus.”

Brian Lovett, Ph.D., a co-author of the study, further explained to VERIFY what makes the fungus-infected cicadas hypersexual.

“This fungus keeps cicadas alive during infection, so it uses infected, but still living, cicadas as a vehicle for infecting others. One opportunity for infection is when an uninfected cicada attempts to mate with an infected cicada. This means that hypersexuality benefits the fungus because it would increase transmission,” he said.

While it’s been verified that it’s safe for humans and animals to eat healthy cicadas, Lovett says he and his colleagues do not recommend humans or animals to eat zombie cicadas.

“While we believe it would be safe for someone to accidentally consume a zombie cicada, we do not recommend eating them. They produce a variety of chemicals to manipulate their cicada hosts, but they produce these at very small doses. These doses are sufficient to affect cicadas, but would likely not affect us,” he said.

When asked if eating a zombie cicada would affect consumers like magic mushrooms, Lovett noted that “massospora that infects periodical cicadas like Brood X produce cathinone, an amphetamine, not the ‘magic mushroom chemical’ psilocybin.” He did, however, say that annual cicadas can become infected with Massospora species that produce the second chemical.