The Burnout Equation: America’s Teacher Shortage Crisis

Amid a nationwide teacher shortage, one question looms — who is going to teach America’s children when educators burn out?

Research has found that teachers matter more to student achievement than any other aspect of schooling. But after decades of insufficient pay and increased workloads, many teachers across the United States have had enough.

“I need a pep talk right now because I'm not sure if I can come back on Monday at this point,” Violeta Duran, a high school English teacher in Los Angeles County, California, told VERIFY.

Duran, who has worked as a teacher for nearly 20 years, said she’s burned out. She’s not alone. Teachers in K-12 education report significantly higher rates of burnout than full-time workers in any other industry, including other high-stress professions like healthcare and law, according to a 2022 Gallup poll.

“I've been burned out for quite some time,” Joaquín Rodriguez, a high school multilingual science teacher in Seattle, Washington, said. “That stress is compounding.”

VERIFY spoke to several current and former teachers who say they are burning out for two main reasons: being overworked and underpaid. While teachers say those factors aren't new, they've reached a breaking point — a breaking point that might cause teachers to leave the classroom for good.

THE SOURCES

- U.S. Department of Education

- U.S. Department of Labor

- National Center for Education Statistics

- Gallup

- National Education Association

- McKinsey & Company

- RAND Corporation

- Center on Reinventing Public Education

- Center for American Progress

- The Education Trust

- Transcend

- The White House

- The American Rescue Plan Act

- Richard M. Ingersoll, Ph.D., professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania

- Heather Peske, Ph.D., president of the National Council on Teacher Quality

- Diana Hess, Ph.D., dean of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Education

- Steve Karlin, Ed.D., retired superintendent of Garden City Public Schools in Garden City, Kansas

- Adrian Howie, superintendent of Hugoton Public Schools USD 210 in Hugoton, Kansas

- Violeta Duran, high school English teacher in Los Angeles County, California

- Sarah Kois, former band director in Akron, Ohio

- Joaquín Rodriguez, high school multilingual science teacher and Seattle Education Association Center for Racial Equity coordinator in Seattle, Washington

- Evin Shinn, instructional coach at Washington Middle School in Seattle, Washington, and former middle and high school teacher

Chapter 1 Overworked and Underpaid

High school English teacher Violeta Duran started teaching in 2005. Since then, she says her salary hasn’t kept up with the cost of living.

“My pay since I started has not quite doubled — but my rent has tripled,” Duran told VERIFY.

During the 2020-2021 school year, the average teacher salary in the U.S. was $66,432, according to the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union. This means that teachers are bringing home on average $2,179 less per year than they did 10 years ago when adjusted for inflation.

In addition to insufficient pay, teachers report that their workload has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic started in March 2020.

According to surveys conducted in October 2020 by the RAND Corporation, 57% of teachers reported working more hours per week than they had pre-pandemic, with teachers reporting they worked six more hours per week on average. Nearly half of all the teachers surveyed reported working a total of 48 hours or more per week, while 24% reported working an average of 56 or more hours per week.

Research and consulting group McKinsey & Company also found that on average, K-12 students fell behind by five months in math and by four months in reading at the end of the 2021-2022 school year. This has caused many teachers, like Duran, to dedicate more time each week to help their students catch up.

“Last year, in particular, very much felt like first-year teaching all over again,” Duran said.

Data released by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) found that nearly half of all public schools across the country reported full or part-time teaching vacancies that they could not fill in 2022 due to the pandemic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a staffing shortage in the nation’s schools. Public schools report they are struggling with a variety of staffing issues, including widespread vacancies, and a lack of prospective teachers. These issues are disrupting school operations,” NCES Commissioner Peggy G. Carr said in March 2022.

Carr added that many schools have resorted to using more teachers and non-teaching staff outside of their intended duties, which has led to larger class sizes in schools, and less support for the teachers.

A 2022 survey from the National Education Association, for example, revealed that more than half of its members said they were more likely to quit or retire from teaching early due to ongoing job stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The impact is massive,” Duran said. “Every student you add on top of that exponentially increases the difficulty in being able to aid every student.”

Chapter 2 The Race Factor

Both pay and workload issues are worse for teachers of color.

Black teachers earn an average of $2,700 less per year than white teachers, and teachers in high-poverty schools earn about $4,000 less than teachers in low-poverty schools, according to a 2019 Center for American Progress study. Black teachers disproportionately teach in high-poverty schools, which means that wage gaps can be more significant for them.

Teachers of color told VERIFY they often have to take on extra responsibilities in addition to teaching when compared to their white colleagues. Former middle school teacher Evin Shinn said his white peers often asked him for help to discipline students of color in their classrooms just because he is Black.

“It wears on you. It becomes a brown-and-black tax on educators,” Shinn said.

Shinn, who taught middle and high school for about 12 years, now works as an instructional coach at Washington Middle School in Seattle. In his current position, he provides mentorship and guidance to teachers in the classroom.

A 2018 Education Trust study of 90 Latino teachers found a similar pattern. Many of the Latino teachers the Education Trust surveyed reported that they often took on extra responsibilities, such as translating and editing materials for their school or the entire school district, without earning additional compensation.

“Oftentimes educators of color are returning to the scene of the crime, so to speak. They were students in our school system or students in school systems… where they felt, oftentimes very under-supported,” high school multilingual science teacher Joaquín Rodriguez said.

Chapter 3 Leaving the Classroom

Regardless of race, teachers burning out and leaving the profession is nothing new.

Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania who studies trends in the teaching workforce, found that for the last 20 years, “between 40% and 50% of those that go into teaching are gone within the first five years.” His research still supports this statistic today.

What’s different now? The teaching pipeline is drying up.

“We're losing teachers faster than we can get new ones in,” Adrian Howie, superintendent of Hugoton Public Schools in Hugoton, Kansas, told VERIFY.

Most states require teachers to have at least a bachelor’s degree to teach at any grade level. In 2010, the Indiana Business Research Center found that nearly 72% of elementary school teachers had a bachelor’s degree in education.

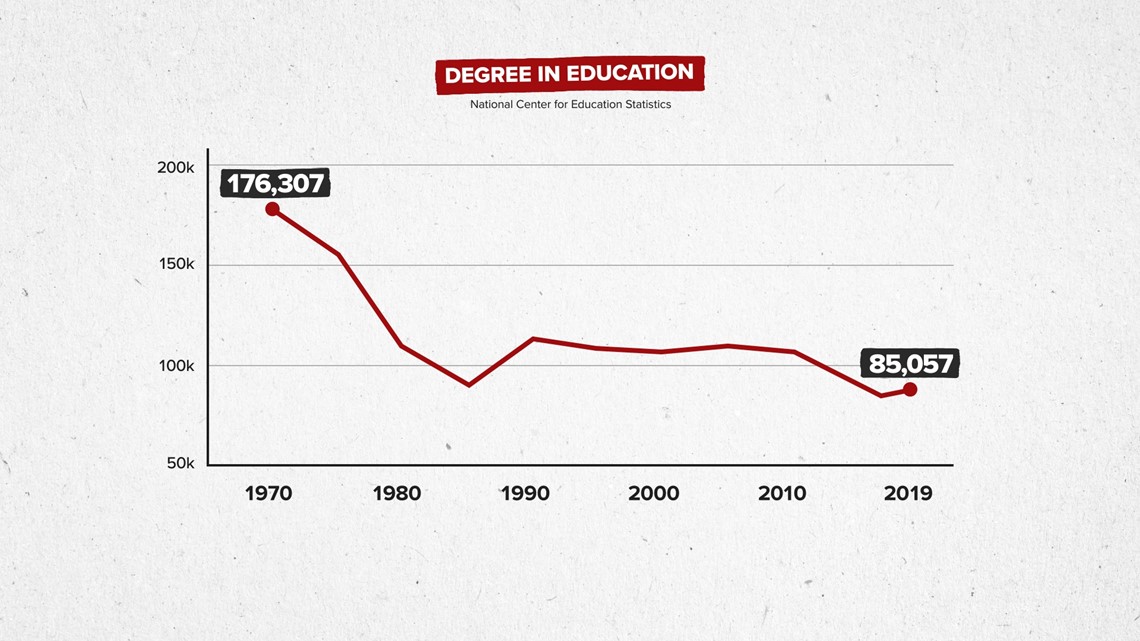

But the percentage of college graduates earning a bachelor’s degree in education is roughly half of what it was in 1970 — dropping from 176,307 to 85,057 in 2019, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

“I feel like teachers have been screaming there's a crisis, and nobody's listening,” Duran said.

Chapter 4 Lowering Standards

Many school districts across the country are looking for ways to combat the teacher shortage crisis.

In some states, one strategy has been “lowering standards and lowering requirements for entry into teaching,” according to Heather Peske, the president of the National Council on Teacher Quality.

In addition to having a bachelor's degree, most states used to require teachers to pass a teaching certification exam before being allowed to teach. But Peske says at least 12 states have recently removed or lowered the requirements for teachers to get that certification since 2020.

This means teaching candidates who don’t pass the state exam could still be given a license to teach in places like Alabama and Missouri. In July 2022, the Alabama State Board of Education voted to change teacher certification requirements due to severe staffing shortages in many schools throughout the state.

“When you’re in a crisis, you tend to do things that you probably would not ordinarily do. I think this will definitely bring some relief without compromising the quality of education,” Tonya Chestnut, a board member for Alabama’s State Board of Education, said.

But Shinn told VERIFY he worries that lowering teaching standards will result in students getting underqualified teachers.

“We are just putting people in classrooms that are not credentialed or who are not ready to be in the classroom. But because of the fact that we're looking for a warm body, we are saying, like, ‘Oh, okay, well, good enough,’” Shinn said.

Peske also thinks lowering teaching standards is the wrong approach.

“This will result in a less effective teacher workforce,” Peske said. “That's the opposite of what our students need, particularly now on the heels of this pandemic.”

University of Pennsylvania professor Richard Ingersoll says lowering teaching standards will only make more teachers leave the profession.

“Generally, the less prepared people — the emergency and temporary licenses, for instance, that are issued — those people quit at higher rates,” Ingersoll said.

Chapter 5 Testing Solutions

Educational nonprofits are also trying to find solutions to help teachers enter and stay in the profession.

Transcend, which works with schools nationwide, told VERIFY they've seen success moving coaches and parents into short-term teaching positions to ease the burden on full-time staff.

“Now more than ever, we need to be running toward solutions to reimagine student learning and to reimagine the people who serve them as their teachers,” Jenee Henry Wood, Transcend’s Head of Learning, said.

Steve Karlin, a recently retired superintendent of Garden City Public Schools in Garden City, Kansas, had a similar idea nearly 15 years ago.

Back then, Karlin said his school district’s open teaching positions were mostly in high school math and science. To fill those roles, he said that he’d typically take elementary school teaching candidates who didn’t have a classroom yet and put them in high school classrooms after paying for their training. That strategy worked until about 2016, he said.

“We haven't been able to utilize that strategy because we can't even fill all of our elementary classrooms,” Karlin said.

Karlin then tried dipping into the substitute teacher pool in order to fill open teaching positions, but he says that pool eventually dried up in his school district as well.

“It's a crisis in my opinion, and… it's not going to get better without taking some intentional steps to make it better,” Karlin said.

Chapter 6 “Let’s give teachers a raise.”

While school districts and educational nonprofits are looking for ways to keep teachers in the classroom, the federal government and some universities are trying to address the teacher shortage crisis with money.

In March 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act allocated $130 billion to K-12 schools nationwide. The White House says schools can use that money to invest in teacher pipeline programs, increase teacher salaries and hire more teachers.

The U.S. Departments of Education and Labor issued a joint letter to state lawmakers and administrators in August 2022 urging them to use the relief money to increase pay for teachers.

Two proposals, the American Teacher Act and the Pay Teachers Act, which were introduced in the House and Senate in early 2023, also aim to raise teacher salaries. If passed, the legislation would set a minimum starting salary of $60,000 for all U.S. public school teachers. That’s far higher than the national average starting teacher salary of $41,770 in the 2020-21 school year.

Neither bill has been voted on so far, but bipartisan support for both is growing. As of May 2023, the American Teacher Act, which was reintroduced in the House in February, has more than 50 co-sponsors. Meanwhile, the Pay Teachers Act, which was introduced in the Senate in March, is backed by seven co-sponsors and has the support of more than 50 major education organizations.

Meanwhile, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Education is using private funding from alumni and supporters to incentivize more people to become teachers.

“We're saying to any student who wants to come into any of our 15 different teacher education programs, that we will pay the cost of their tuition, their testing fees and their licensing fees,” Diana Hess, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Dean of Education, told VERIFY.

In exchange, Hess says the students who receive money from the university must pledge to teach in Wisconsin public schools for three to four years after graduation. The $25 million dollar privately funded program, which launched in August 2020, also offers mentorship and professional development support for alums.

Sarah Kois is a former band director in Akron, Ohio, who quit the teaching profession in 2021. She said she wishes she had that kind of support during her early years of teaching.

“I think people think, ‘Oh, after your second or third year, you're good to go. You're a pro.’ But I think that those supports need to stay in place,” Kois said.

Duran says she’d like to see the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s pledge program be adopted by more schools nationwide.

“I see it as a positive, like any program that can do that. I mean, it would be great,” Duran said.

Nevertheless, although educators like Duran, Rodriguez and Shinn may be suffering from burnout, they’re not leaving the profession.

When asked why she’s staying, Duran told VERIFY, “At the end of the day, it’s the students. There’s an energy that they bring that is unmatched… I see something often planted in them that they don't even see sometimes, and that I think gives me hope.”

Credits:

- Ariane Datil, VERIFY Host

- Eric Garland, Producer/Editor

- Erin Jones, Digital Journalist

- Mauricio Chamberlain, Researcher

- Francis Abbey, Photojournalist

- Amie Casaldi, Creative Lead/Sr. Motion Designer

- Eleni Hosack, Producer/Editor, Graphics

- Jonathan Forsythe, Managing Editor

- Erica Jones, Deputy Editor

- Sara Roth, Senior Editor, Digital

- Lindsay Claiborn, Senior Editor, Video

- Megan Yoder, Digital Audience Editor

- Amanda Lashbaugh, Audience Engagement Producer