February is Black History Month, which is a time to honor and acknowledge notable Black Americans and their contributions to society.

In 2022, a thread on Twitter shared during Black History Month claimed that the nation's first paramedics were a team of Black men.

A paramedic is a healthcare professional who is trained to give emergency medical care to people who are injured or ill, typically as they are transported to the hospital.

THE QUESTION

Were the first paramedics in the U.S. Black men?

THE SOURCES

- University of Pittsburgh

- The City of Pittsburgh

- National EMS Museum

- Senator John Heinz History Center

- EMS1 & National EMS Management Association (NEMSMA)

- Kevin Hazzard, writer, former paramedic and author of “American Sirens”

THE ANSWER

Yes, the first paramedics in the U.S. were Black men.

WHAT WE FOUND

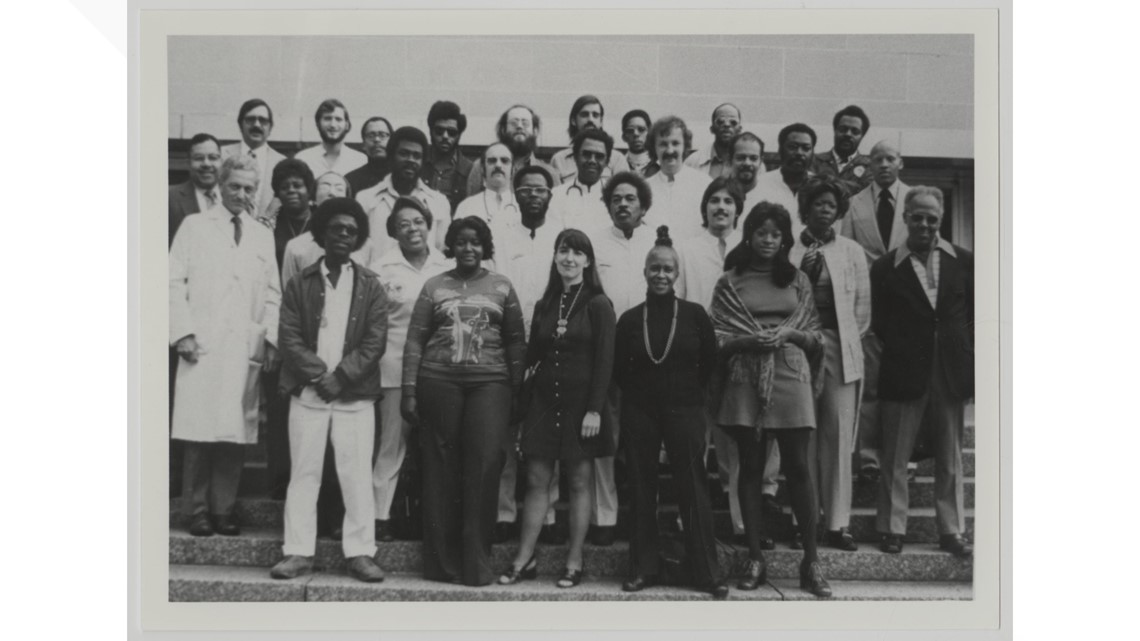

The first paramedics in the United States were a team of Black men who worked for the Freedom House Ambulance Service in Pittsburgh during the 1960s and ‘70s. According to the City of Pittsburgh and the Senator John Heinz History Center, Freedom House was the first ambulance service in the country to provide emergency medical services beyond basic first aid, and it “set the standard for emergency care” for programs nationwide.

Before paramedics existed in the U.S., the police, volunteer firefighters, funeral directors and private companies were typically responsible for responding to emergencies. Most of these first responders were not medically trained and had outdated or minimal medical equipment in their emergency vehicles, according to Kevin Hazzard, a former paramedic and author who wrote “American Sirens,” a book that details Freedom House’s story, and a 2011 article on the University of Pittsburgh's website. This often led to many people in medical distress dying en route to the hospital.

“They would arrive at your house, they would pick you up, they would load you in the back, they would close the doors and then the two of them would hop up front and you would ride alone in the back. So it was quite literally just a ride,” Hazzard told VERIFY. “The result of that was a tremendous amount of unnecessary death in the United States.”

In September 1966, a report titled "Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society," documented the lack of emergency medical care and health disparities in the U.S. This report found that Black Americans "had the least access to emergency medical care in the nation, resulting in a public health crisis,” according to the Heinz History Center.

Pittsburgh's largest Black neighborhood, known as the Hill District, "suffered most acutely from this crisis," the Heinz History Center says on its website. This was because a majority of the residents in the Hill District fell far below the poverty line, and had to fight constantly against racial injustice, according to the National EMS Museum.

“Many of the residents [of the Hill District] were deemed ‘unemployable’ by the city welfare offices and had bleak prospects for long-term stability,” the National EMS Museum says on its website.

A few months after the report was released, former Pennsylvania governor and Pittsburgh mayor David L. Lawrence suffered a heart attack while giving a speech on Nov. 4, 1966. He was transported to the hospital in a police emergency wagon or paddy wagon.

The University of Pittsburgh says a nurse who was in the crowd performed CPR and accompanied Lawrence during the transport, only to find a broken inhalator/resuscitator in the vehicle. The vehicle also swayed back and forth so much during the ride that the nurse kept losing her balance and was unable to continue CPR.

When Lawrence arrived at the hospital, his brain had been deprived of oxygen for too long and he suffered permanent brain damage, according to the University of Pittsburgh. He never regained consciousness and died two weeks later on Nov. 21, 1966.

Not long after Lawrence’s death, Phil Hallen, a former ambulance driver and activist, who served as president of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, a local philanthropy, came up with the idea to start a private ambulance service in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Hallen presented his idea at Presbyterian University Hospital, and they introduced him to Peter Safar, M.D., an Austrian-born anesthesiologist who is known as the “father of CPR.”

Hallen and Safar developed a plan to recruit unemployed Black men from the Hill District who, after receiving extensive emergency medical training, would work as the first paramedic team in the U.S. With the help of James McCoy Jr., a local steelworkers union leader, community activist and founder of Freedom House Enterprises, their idea was brought to fruition in April 1967, and the Freedom House Ambulance Service was officially established as a private-public partnership with the City of Pittsburgh.

"Dr. Safar's first class of 20 African American men graduated the first round of medical services studies and began nine months of on-the-job training running two second-hand police ambulances donated by the city," the University of Pittsburgh says on its website.

In its first year, the Freedom House Ambulance Service made 5,868 responses to emergency calls and transported 4,627 patients to the hospital from the Hill District and downtown Pittsburgh. The paramedics responded to an average of 15 calls a day, and only 1.9% of those patients died before arriving at the hospital, according to the University of Pittsburgh.

“It is instantly recognized as a success,” Hazzard said. “It is such a success that other cities begin arriving and borrowing bits and pieces, doctors come to see what they're doing and are so incredibly impressed with the program that they bring as much of it back home with them as they can.”

Despite the ambulance services' many successes, in 1974, Pittsburgh mayor Peter Flaherty announced that the city would be starting its own EMS training program and would not be renewing Freedom House’s contract. Hazzard says Flaherty, who was an opponent of private-public partnerships like Freedom House, decided to disband the program due to lack of funding and racism.

“In 1974, the city decides, finally, to create its own EMS program, and they dumped tons of money into it, and they buy tons of equipment, they hire all kinds of people, and they're all white,” Hazzard said. “So suddenly, they have the money, they have the will, they have the people, they have, you know, the desire to do it. They just didn't have the desire to do it when the people doing it were Black. That's a very difficult thing to deny.”

On Oct. 15, 1975, the Freedom House Ambulance Service took its last call. During the ambulance service’s eight-year history, the Freedom House paramedics handled more than 45,000 emergency calls throughout the Hill District, and eventually, the entire city of Pittsburgh, according to the University of Pittsburgh.

Nancy Caroline, M.D., a physician whom Safar appointed as Freedom House’s medical director in 1974, was asked to lead the City of Pittsburgh’s EMS program. She tried her best to push the city to hire the Freedom House paramedics.

“The city was so poorly prepared to make this transition, that they had no choice but to turn to Nancy Caroline. And they said, ‘Look, we need your help.’ And she said, ‘Fine, I'll come over and I'll help you create your new service, even though we have one already, but in order for me to do that, I need to know that you're going to hire all of my people,’” Hazzard said.

The city agreed to hire the Freedom House paramedics, but Hazzard and the National EMS Museum both say many of them were reassigned to non-medical duties or decided to leave the emergency services industry altogether.

“They cut Freedom House’s ranks by about 50% within a year. And, you know, through the course of the next several years continued to weed people out. Some of them stayed and went on to have very distinguished careers, but a lot of them did not,” Hazzard said.