Ian has since been downgraded to a tropical storm after making landfall in Florida as a dangerous Category 4 hurricane on Wednesday, Sept. 28.

The hurricane was one of the strongest to ever hit the United States, leading to widespread flooding and knocking out power to millions of Florida homes and businesses.

As the hurricane approached Florida’s Gulf Coast on Wednesday, viral videos shared on Twitter and TikTok showed water apparently being “sucked out” of Tampa Bay instead of rushing into the area and flooding the shore.

THE QUESTION

Was water “sucked out” of Tampa Bay by Hurricane Ian?

THE SOURCES

- NOAA National Hurricane Center

- Matthew Bilskie, Ph.D., assistant professor at the University of Georgia’s College of Engineering and hurricane storm surge modeler

- Tampa Bay Police Department

- Florida Division of Emergency Management

THE ANSWER

Yes, water was “sucked out” of Tampa Bay by Hurricane Ian. This is a phenomenon often called “reverse storm surge,” experts say.

WHAT WE FOUND

Florida authorities warned people as Hurricane Ian neared landfall on Wednesday not to walk out into the receding water in Tampa Bay.

“The water WILL return through storm surge and poses a life-threatening risk,” the state’s Division of Emergency Management wrote in a tweet.

Tampa Bay police also said in a tweet that officers were telling people to leave Bayshore Boulevard, a waterfront road in Tampa Bay, “due to people coming out to see or walk on the low tide.”

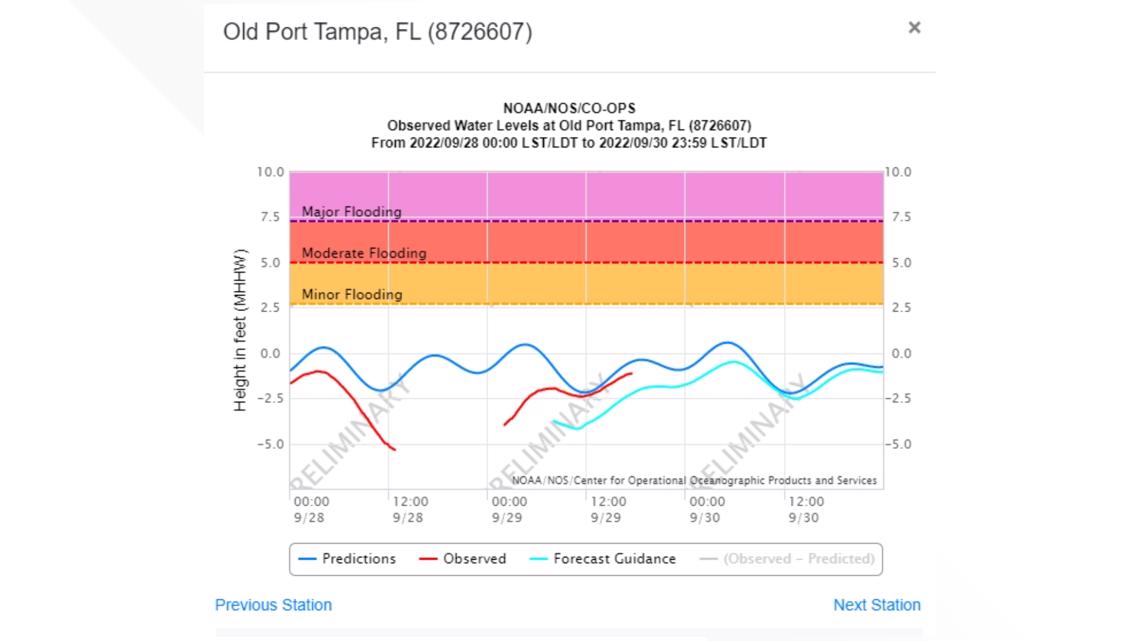

In an email to VERIFY, a spokesperson for the NOAA National Hurricane Center (NHC) confirmed that water receded from the bay during Hurricane Ian due to a phenomenon often called “reverse storm surge.” Water levels observed by NOAA in Tampa Bay show values going negative beginning Wednesday morning, meaning the water was pulled away from the coast.

Water levels in Tampa Bay mostly returned to normal by Thursday morning and the area was largely spared from the hurricane’s impact.

So what is reverse storm surge? In simple terms, it is what it sounds like – the opposite effect to storm surge or a “drawdown of the surge,” Matthew Bilskie, an engineering professor and hurricane storm surge modeler, explained.

NHC explains that storm surge is an “abnormal rise of water generated by a storm” above the predicted tide. It is caused primarily by strong winds in a hurricane or tropical storm, and generally occurs where winds are blowing onshore.

Reverse storm surge is also driven by the direction of the wind. In the case of Hurricane Ian, wind was moving from the northeast to the southwest, pulling water away from Tampa Bay, according to Bilskie.

“That’s causing the water to leave Tampa Bay because you have the wind essentially in the same direction as the exit to the bay,” he said. “The water is going to go typically where the wind is blowing in these large wind scenarios, like during hurricanes. So when you have a sustained wind over several hours – in this case, likely almost a full day of wind moving in that direction – it is going to push that water back out into the ocean.”

Water also receded out of Tampa Bay during Hurricane Irma in 2017, Bilskie said. But that doesn’t mean this will always be the outcome for the area during a major storm.

“I just want folks to realize that this [reverse storm surge] isn’t going to happen every time because the last two storms, Irma and now Ian, caused that to happen,” he said.

Bilskie reiterated that it’s dangerous for people to stand or walk on the bay in the event that storm surge returns.

“Once the wind changes direction, or the wind dies down, then that surge is no longer being held back by the ocean from the wind,” he said.

Though the water won’t rush back in “like a tsunami,” it could return over “just a few short hours” and “certainly catch people off guard,” Bilskie added.